Mahmood, Cinderella, and a fairytale with a happy ending

Mahmood, Cinderella, and a fairytale with a happy ending

Everyone loves a Cinderella story. Rags to riches, the girl gets the prince and all that jazz. I love Cinderella stories too. Always have. Not only as a kid, but as a grown-up (and a geeky one at that), which means lots of reading and obsessing and researching. Can I tell you a secret? Cinderella isn’t really about being poor and becoming rich, nor is it about getting the prince at the end. It’s about other things that make our daily lives, struggles and dreams what they are, which is why the story has been such a popular one throughout history: on a basic human level, we all share some of the same wants and needs. We want to be accepted. We want to be loved. And we want it to be for the person we really are.

In the age of technology, social media and betting odds, it’s hard to find a Cinderella narrative that isn’t intentionally driven by a TV show’s production team – particularly if it’s an event that stretches over a period of time, like the Eurovision Song Contest or its esteemed older relative, the Sanremo Festival. There’s simply too much data out there – views, sales, trends, social media trackers – that even with the random factor of the juries, it’s hard to end up with a truly surprising winner.

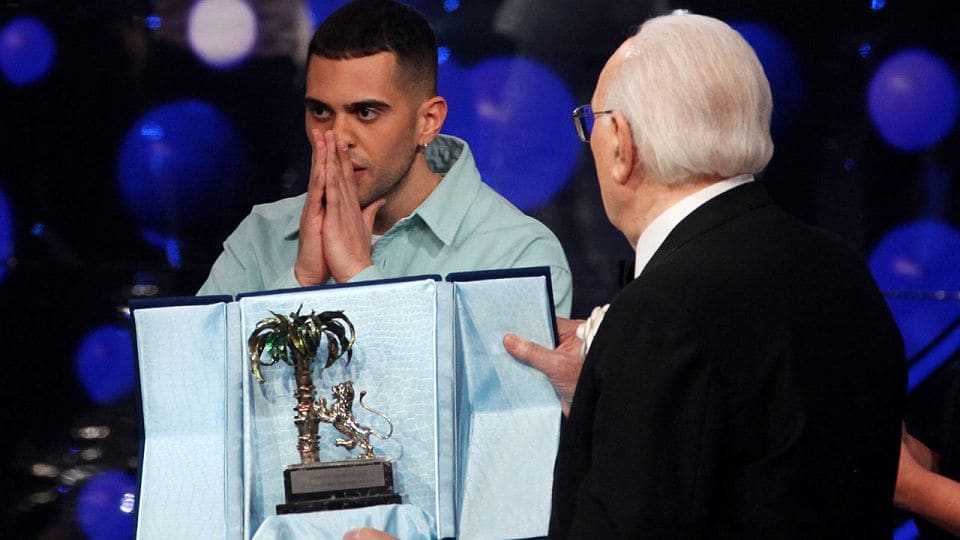

But just because some things rarely happen doesn’t mean they can’t. As one of my favorite bookish quotes goes: “When people say impossible, they usually mean improbable”. And improbable is a good way to describe Mahmood’s win at Sanremo 2019.

It started where all fairytales do: with an absent parent. We are all born to someone, and as fairytales often remind us, the circumstances of our birth – who our parents are, where were we born, the people we grow up around – lie out of our control. But no matter how old those stories are, one thing holds true: a dysfunctional or a broken family is a challenge for anyone to overcome. Fathers in particular are barely mentioned in fairytales. They sometimes appear at the beginning, but the story gets rid of them soon afterwards. Or they are there, but as useless figures who contribute nothing to the story and the lives of those around them. Still, mostly they are absent – and it’s that absence that places the protagonist in the predicament of their tale. For Cinderella, the untimely death of her father and his unfortunate taste in second wives left her at the hands of an abusive step-parent. As for Mahmood… well, let’s just say that while he wrote an entire song about his relationship with his dad, it’s notable that, just like in the fairytales, the dad is an absent figure. Not just from his life, but more or less from his song too. In contrast to all the other songs devoted to loving fathers that we’ve encountered during this 2019 national final season, “Soldi” mentions the word “dad” only once.

A common misconception of Cinderella is that it’s a shallow story about how wearing a gorgeous gown and having a great hairdo can make any prince fall in love with you in five seconds flat. But it’s not. It’s about having your potential recognized even when you feel entirely out of your depth. The right dress, shoes and hairstyle are just the entrance ticket to the ball, one that Cinderella never attended in the hope of catching herself a prince. She just wanted to live a little and do something she’d probably never get the chance to do again. Carpe diem, you know? She does end up in the center of a competition of sorts, but not one she imagines she could ever win – in a theoretical Betfair market on “girl most likely to capture the prince’s heart”, she wouldn’t even feature on the list – so she just allows herself to enjoy the moment.

Not all Cinderellas are the same

Sanremo 2019 wasn’t much different to the prince’s ball, pretty gowns notwithstanding. This year’s revised format with 24 songs, including two entries that qualified directly from Sanremo Giovani in December, meant both Mahmood and Einar – the other qualifier, who actually won the young competition – had a lot of catching up to do. The line-up was packed full of household names with decades of experience. Everyone, even the younger ones, have multiple albums behind them, while Mahmood and Einar are only just about to release their first. And sure, Sanremo is a song contest first and foremost – but when the audience tunes in for the week-long TV extravaganza, they’re keen to see what their favorite artists will do, what Loredana or Nek or whoever has brought this year. At Eurovision, a casual viewer might be eagerly anticipating a song they’ve heard is the big favorite or a former pop star they recognize, but that’s one or two out of a field of 26 – the rest all have an equal chance to catch their attention. At Sanremo this year, it was the opposite: almost everyone started from a position of viewer familiarity. Except two.

This is where the juries come in. The reasons might be different, but like at Eurovision, the juries are there to consider the songs and put aside other elements like pre-existing popularity. There’s no fairy dust involved as far as I know, but still, it’s a bit like the intervention of the Fairy Godmother (often veiled as a cranky old lady, much like some jury members) who sees the true potential behind all the distractions.

Cinderella’s outsider status wasn’t just due to being unknown. Social class plays a major part in her story, and her perceived place in society is low enough for her to be considered a second-class citizen. In many versions she is actually a noble-born, reduced in status by her step-family, and much of the tale is about how easy it is to simply see what we expect to see – and how hard to realize the truth is often more complicated and identity is complex.

Prince Charming

In today’s real-life world, it’s often less about class and more about race, heritage and citizenship status. Alessandro Mahmood was born in Milan 26 years ago to an Italian mother and an Egyptian father. And yet after Sanremo, instead of talking about his remarkable win, he found himself involved in discussions about what percentage of him is Italian. The answer being “100%”, needless to say. But merely having that dash of the exotic in his Italian-Egyptian heritage and including a few words in another language in his song – apparently the only ones he knows in Arabic, a leftover of his childhood with his father – are enough to bring up this obviously loaded question.

The way Mahmood put himself out there – his identity as an artist, the story in his song, and the way he was seen by the press, the juries, and some of the audience too (after all, he ranked fairly high during the week in terms of the televoting ranking as well as online views and streams) – reminded me of the ending of Cinderella, when the prince finds her, back in her position as servant, and it turns out it makes no difference to him at all: she’s still her.

I always write that I want to see countries sending entries that really represent them. While Italy could never be accused of sending anything other than that, simply because of the sheer popularity of Sanremo, the festival itself tends to suffer from a similar problem to Eurovision: entries that sound like they were specifically made for the competition. We don’t often get Sanremo songs that sound so unlike Sanremo, and it’s even rarer for Italy to offer a Eurovision entry that is so current.

There was a lot of talk right after the festival about the fact that “Soldi” didn’t do well in the televote and what that means for its chances at ESC. But looking at the numbers from during and after the festival, I think it mostly says a lot about the circumstances of the festival and less about the song itself. While it’s natural for there to be some interest in the winner, an unpopular winner with the public – and there have been some before – would typically be reflected in the numbers. Yet they show the opposite: “Soldi” has racked up 28 million views for its official YouTube clip and millions more across the other live performances, while it’s been leading the streaming charts every day for the past few weeks, averaging almost 1.5 million streams a day during the first week after Sanremo and actually breaking the Italian record. Mahmood has also been at number one in the official Italian chart every week since.

So whatever manufactured controversies there may have been along the way, it turns out the fairytale has a happy ending. As it should! After all, Cinderella had so much fun at the ball that she never wanted to leave – and the Italians seem to be fine with Mahmood’s fairytale continuing all the way to Tel Aviv.

And as Jeanne Moreau once said: “While Cinderella and her prince did live happily ever after, the point, gentlemen, is that they lived.”

Visit our Eurovision Chat!

0 Comments

Visit our Eurovision Chat!

Follow us:

RetroSongHunt 2004: Join us as we celebrate 20 years of #esc!

Our chat community celebrates its 20th anniversary on the first weekend of June – so what better way to celebrate than with a special chat event dedicated to national final songs from back when we began? Read all about it here!

Who will win the Eurovision Song Contest 2024? Our prediction for the final

Happy Eurovision – the big day has arrived! Tonight the grand final of ESC 2024 will be held in Malmö, Sweden. But who will hold the trophy at the end of the show? It’s time for our team’s predictions!

The View from Israel: Unforgettable

There’s one more night left for Eurovision 2024, and Shi is hoping we can all enjoy it a little.

Overthinking the 2024 grand final running order

As the dust settles on the second semi-final, Martin takes a look at what the producers have come up with for the ESC 2024 grand final running order and what – if anything – it might mean…

ESC 2024: The escgo! predictions for tonight’s semi-final 2

Let the team predictions continue! These are the songs that Felix, Shi and Martin think will qualify from tonight’s second semi-final of the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest.

The View from Israel: We rum-de-dum-dum-da

The View is back for Eurovision 2024! Different location, same overthinking – and now it’s time for the second semi-final.

ESC 2024: The escgo! predictions for tonight’s semi-final 1

It wouldn’t be Eurovision without some predictions from our team! These are the songs that Felix, Shi and Martin think will qualify from tonight’s first semi-final.

The View from Israel: Whеn the stars align then I’ll be thеre

The View is back for Eurovision 2024! Different location, same overthinking – starting with the first semi-final!

Gåte from Norway are the winners of ChatVote 2024!

The 20th annual edition of ChatVote is over, and the best song in the forthcoming Eurovision Song Contest is the one from…

ChatVote 2024 is launched! Once again: One Night. One Winner.

It’s time for the 20th edition of our legendary annual event. For our chat regulars, the lines are now open for you to submit your votes!

RetroSongHunt 2004: Join us as we celebrate 20 years of #esc!

Our chat community celebrates its 20th anniversary on the first weekend of June – so what better way to celebrate than with a special chat event dedicated to national final songs from back when we began? Read all about it here!

Who will win the Eurovision Song Contest 2024? Our prediction for the final

Happy Eurovision – the big day has arrived! Tonight the grand final of ESC 2024 will be held in Malmö, Sweden. But who will hold the trophy at the end of the show? It’s time for our team’s predictions!

The View from Israel: Unforgettable

There’s one more night left for Eurovision 2024, and Shi is hoping we can all enjoy it a little.

Overthinking the 2024 grand final running order

As the dust settles on the second semi-final, Martin takes a look at what the producers have come up with for the ESC 2024 grand final running order and what – if anything – it might mean…

escgo! on Twitter

0 Comments